Art Nouveau: A Complete Guide to the Style, the Makers, and Where to See It Today

At a glance Art Nouveau (French for “new art”) swept across Europe and the United States from the 1890s to the eve of World War I. Its signature is the sinuous, organic “whiplash” line and a belief that beauty should infuse everyday life—from posters and type to glass, furniture, and the very entrances to a city’s subway.

Definition & dates (and the many names of the “new art”)

Art Nouveau is best understood as an international design movement that peaked roughly between the early 1890s and 1914. It prized flowing, asymmetric lines; motifs from plants, insects, and deep-sea life; and a total-design approach that united architecture, interiors, and objects. Regional labels reveal its spread: Jugendstil (Germany), Secession or Sezessionstil (Austria), Modernismo or Modernisme (Spain/Catalonia), Liberty or Stile floreale (Italy). For a concise museum overview and collection highlights, see the V&A’s Art Nouveau page and the Met Heilbrunn essay on Art Nouveau.

How to spot it: the visual language

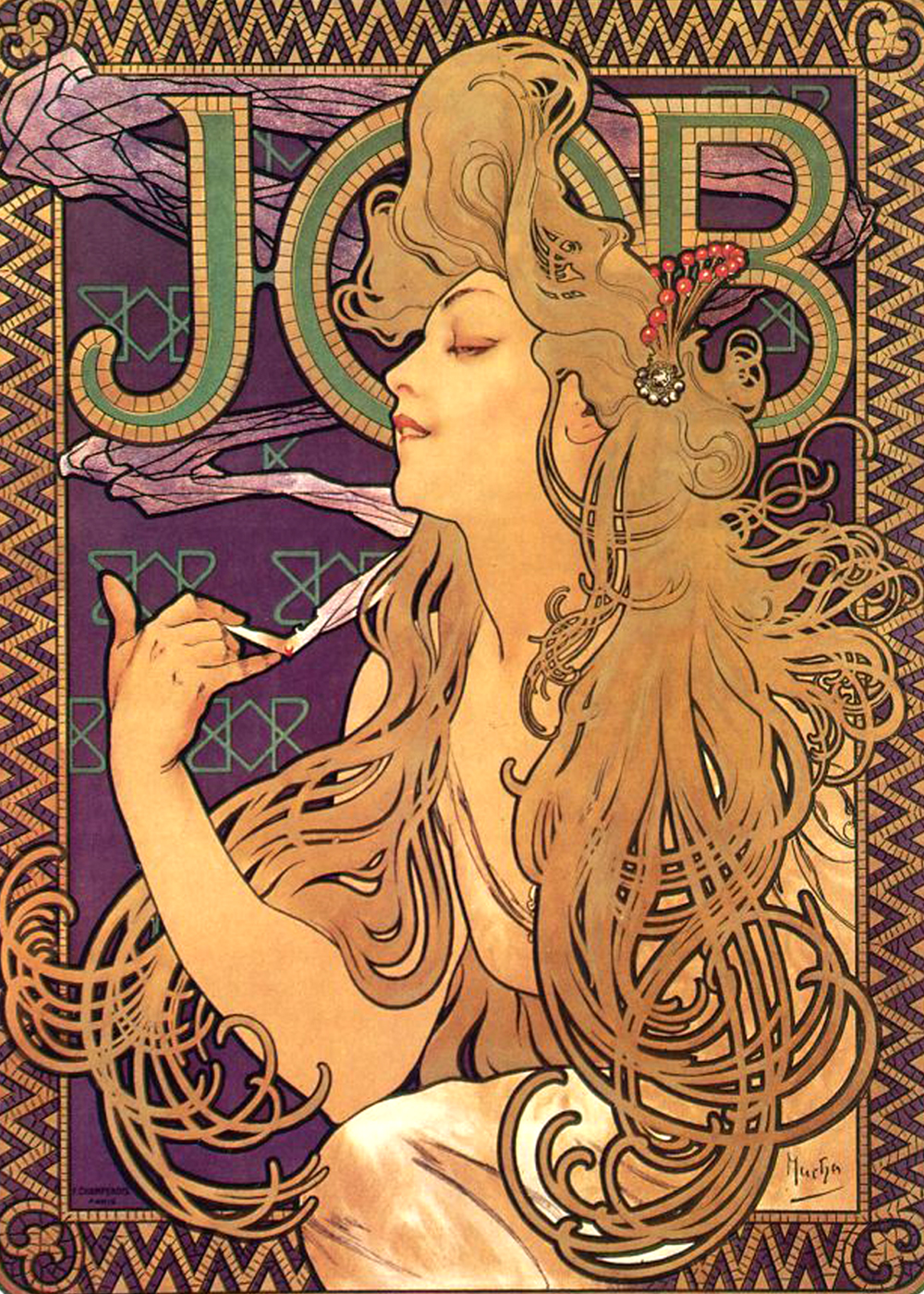

The line comes first. A single curving stroke energizes posters by Alphonse Mucha, ironwork by Hector Guimard, and lettering that seems to grow like vines. Nature is model and metaphor—orchids and thistles in Émile Gallé’s glass, dragonflies and wisteria in Tiffany lamps, the ginkgo crown gilding Vienna’s Secession Building. Typography flexes: letterforms bend, thicken, thin, and interlace, echoing botanical rhythms. Color deepens the mood—smoky purples and greens in lithographic posters; amber, emerald, and opalescent blues in stained glass.

Materials & making: from posters to pedagogy

Art Nouveau never belonged to a single medium. It blossomed simultaneously in graphic arts (lithographed posters, type, book design), decorative arts (glass, ceramics, metalwork, jewelry, furniture), and architecture (curving façades with integrated iron, stone, and stained glass). Teaching resources and exhibition literature emphasize this breadth, making the movement an ideal case study for cross‑disciplinary learning. For an excellent, classroom‑ready entry point, explore the NGA’s Art Nouveau teaching packet (1890–1914).

Case study: Hector Guimard and the Paris Métro

Few designers embody Art Nouveau’s union of structure and ornament like Hector Guimard. His Métro entrances—cast iron sprouting into lily‑like lamps and a custom alphabet for the word “Métropolitain”—turned public transit into urban theater. As scholars and curators note, Guimard’s work pairs sensual form with practical modernity: standardized modules, foundry casting, weatherproof canopies. For scholarship and exhibition context, see the Cooper Hewitt’s Guimard feature. For drawings and interpretive displays on the station entrances, consult the Musée d’Orsay presentation on the genesis of the Métro.

Origins and ideas: what the movement believed

1) Beauty belongs in daily life. Art Nouveau’s rallying cry was the integration of art and life—fine and applied arts reconciled in a single environment. 2) Nature is a teacher. Designers translated botanical structures into new technologies (rolled steel, cast iron, molded glass). 3) Total design matters. From the façade to the cutlery, a project should sing one visual language—what German modernists later called Gesamtkunstwerk.

From Brussels to Barcelona: regional flavors

Brussels saw some of the earliest crystallizations (Victor Horta’s townhouses). Nancy, Paris, and the Côte d’Azur nurtured glass and poster arts; Barcelona’s Modernisme fused sculptural stone with polychrome ceramics; Vienna’s Secession favored crisp geometry and symbolic gilding; Glasgow’s “Four” blended linear elegance with moody symbolism; in the U.S., Tiffany Studios balanced iridescent glass with industrial production. For a cross‑movement comparison that situates Art Nouveau among the 20th century avant‑gardes, see our visual side‑by‑side on De Stijl vs. Constructivism.

Type, posters, and the modern look

Mucha’s posters demonstrate the movement’s graphic toolkit: interlaced letterforms, tiled borders, shimmering hair rendered as arabesque. Lettering and layout became fields for experimentation—an arc that later fed into functionalist typography. If you’re exploring how this vocabulary evolves into the 20th century, jump to our guide, Bauhaus typography examples.

Furniture & interiors: from handcraft to industry

Cabinetmakers such as Louis Majorelle and architects like Guimard designed furniture as fluent extensions of the line. Curved veneers, vegetal marquetry, and iron fitments were not “applied decoration” but carriers of structure and meaning. In Vienna, the Secession and Wiener Werkstätte channelled the ideal into cleaner geometries and superb joinery—an important bridge to modern design and the later debates around ornament. Curious how artists of the next generation reacted? Our Cubism primer shows how flat planes displaced the curving line.

Where to see Art Nouveau today

Paris: explore decorative arts galleries and period rooms at the Musée d’Orsay (Decorative Arts), and seek out surviving Métro entrances in situ. Vienna: the Secession Building remains a living venue (and Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze is on site); the MAK’s Historicism & Art Nouveau collection offers deep holdings from Hoffmann, Moser, and beyond. Barcelona: façades by Gaudí and Domènech i Montaner embody Catalan Modernisme. Brussels: Horta’s townhouses and the Horta Museum are essential. United States: look for Tiffany at major museums and period architecture in Midwestern cities shaped by 1900s prosperity.

FAQ — quick answers

What is Art Nouveau in one sentence?

A late‑19th‑century international design movement defined by the flowing “whiplash” line, nature‑derived motifs, and the fusion of art, craft, and architecture.

When did Art Nouveau start and end?

It flourished from the early 1890s to around 1914, when war and new priorities in modern design pushed tastes toward simpler forms.

Is “Jugendstil” or “Secession” different from Art Nouveau?

They are regional names—Germany’s Jugendstil and Vienna’s Secession—for local variants of the same broader movement.

How is Art Nouveau different from Art Deco?

Art Nouveau favors organic curves and plant forms; Art Deco (1920s–30s) uses streamlined geometry and stepped, machine‑age motifs.

Where can I see iconic architecture by Hector Guimard?

In Paris: the Abbesses and Porte Dauphine Métro entrances, along with facades like Castel Béranger in the 16th arrondissement.

Further reading (specialist picks)

- European Route of Art Nouveau (RANN) guides and city overviews.

- Musée Horta, Brussels — documentation on Victor Horta’s houses.

- BANAD (Brussels Art Nouveau & Art Deco) Festival catalogues.

Tip: pair museum studies with architectural walks; the movement’s full effect comes from experiencing interiors and façades together.

0 comments