Surrealism Timeline for Students: Techniques, Key Works & Study Guide

Why Surrealism still matters in class

Surrealism is the 20th‑century movement that tried to unlock the unconscious—dream logic, chance, and free association—to remake how we see the world. In plain terms: it asks students to look for meaning where sense seems to break. In this surrealism timeline for students, you’ll learn when and how the movement formed, what surrealist techniques actually look like, and a simple checklist for analyzing any work. For quick definitions, see concise glossaries by Tate and MoMA.

Key takeaways (read before class)

- Surrealism begins as a Paris‑based movement formalized by André Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, proposing “psychic automatism” as a method for art and writing; it soon spreads internationally.

- Core methods you’ll see on exams: automatism (automatic drawing/writing), photograms (camera‑less photos), frottage/grattage (rubbing/scraping), exquisite corpse (collaborative drawing), and the surreal object.

- Iconic names: Max Ernst, Man Ray, René Magritte, Joan Miró; don’t overlook women surrealists like Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, and Meret Oppenheim.

- Surrealism’s photography—from rayographs to solarization—made the uncanny central to modern visual culture.

- War and exile in the 1940s shift the center to New York, influencing Joseph Cornell and Arshile Gorky and feeding into Abstract Expressionism.

- Legacy: Global surrealism thrives across Latin America, Egypt, and Japan; recent centenary shows highlight worldwide networks and women artists.

Concise background: The Met—Heilbrunn Timeline overview and Tate—Surrealism.

Before Surrealism (1917–1923): Dada, de Chirico, and the spark

Surrealism emerges from two powerful sources. First, Dada’s anti‑rational stance after World War I demonstrates how nonsense, shock, and chance can upend polite culture. Second, Giorgio de Chirico’s “metaphysical” plazas—with their long shadows, empty streets, and uncanny object pairings—model the dreamlike bafflement Surrealists embrace. A perfect example for class is de Chirico’s The Song of Love (1914), where a classical head, a rubber glove, and a green ball form an impossible still life that feels strangely inevitable. See The Met’s overview of Surrealism’s roots in Dada and the MoMA object page for the painting.

1924: The Surrealist Manifesto & the idea of “psychic automatism”

André Breton’s 1924 manifesto defined Surrealism as a way to express the actual workings of thought—psychic automatism—without the censorship of reason or moral judgment. In practice, that meant automatic writing and drawing, chance operations, unexpected juxtapositions, and playful collaboration. For a short, classroom‑ready definition, see MoMA’s Surrealism term page; for a public manuscript and readable English text, consult the BnF/Gallica manuscript and a university‑hosted PDF of the manifesto (Gallica—Breton manuscript; University of Hawaii PDF).

Early hubs included the journal La Révolution surréaliste (1924–1929), which adopted a sober, “scientific” layout to present scandalous ideas. For coverage images and bibliographic context, see Wikimedia Commons—BNF‑sourced scans and The Met rare books entry.

Surrealism study gallery (classroom‑friendly)

Note: Public domain in the U.S.; other jurisdictions may vary.

The Surrealism Timeline (student‑friendly)

Use this surrealism timeline to anchor names, dates, and methods. Definitions appear inline (e.g., photogram = camera‑less photo made by placing objects on light‑sensitive paper and exposing to light).

1917–1923: Proto‑Surreal seeds

- Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings (e.g., The Song of Love, 1914) influence a generation via uncanny juxtaposition and stillness (MoMA).

- Dada’s anti‑rational spirit (Zurich, Berlin, Paris) models chance, collage, and assemblage that Surrealists adapt (The Met—overview).

- Max Ernst experiments with transfer and collage; Joan Miró simplifies symbols and line.

1924–1929: Formation & experiments

- Breton’s manifesto formalizes the movement; La Révolution surréaliste (1924–1929) provides a platform (see BnF‑sourced scans).

- Automatism takes off: free writing/drawing to bypass conscious control (MoMA—Automatism).

- Man Ray popularizes the rayograph (photogram)—camera‑less images made by arranging objects on light‑sensitive paper (MoMA feature—Champs Délicieux).

1930s: International & interdisciplinary

- Journal Minotaure (1933–39) connects artists, writers, and photographers; see a richly illustrated overview (Coulthart).

- Techniques diversify: frottage/grattage (Max Ernst), decalcomania, surreal objects; women surrealists gain visibility (Leonora Carrington, Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning) (Met overview).

- Photography becomes central: montage and solarization evoke dream/reality unions (Met—Photography & Surrealism).

1940s: War, exile, and New York

- Many surrealists relocate to the U.S. (Peggy Guggenheim’s network, wartime visas); New York becomes a hub.

- Impact on American art: Joseph Cornell’s boxes and Arshile Gorky’s biomorphic forms bridge to Abstract Expressionism (Met—overview).

1950s–1960s: New centers & late Surrealism

- Distinctive strands flourish in Britain and Latin America; exhibitions and journals sustain the network.

- Photographic surrealism continues; camera‑less techniques and darkroom experiments persist.

2000s–today: Global Surrealism’s centenary

- Surrealism’s centenary sparks worldwide shows. The Centre Pompidou’s 2024–25 exhibition foregrounds global networks and women artists (Pompidou centenary page).

- Recent press highlights broader geographies (e.g., Japan, Egypt, Latin America) and new research emphases.

Compare & contrast for exam clarity

Unlike Constructivism’s engineered optimism or Op Art’s optical science, Surrealism courts ambiguity, dreams, and the unconscious.

Surrealist techniques: how they actually made things

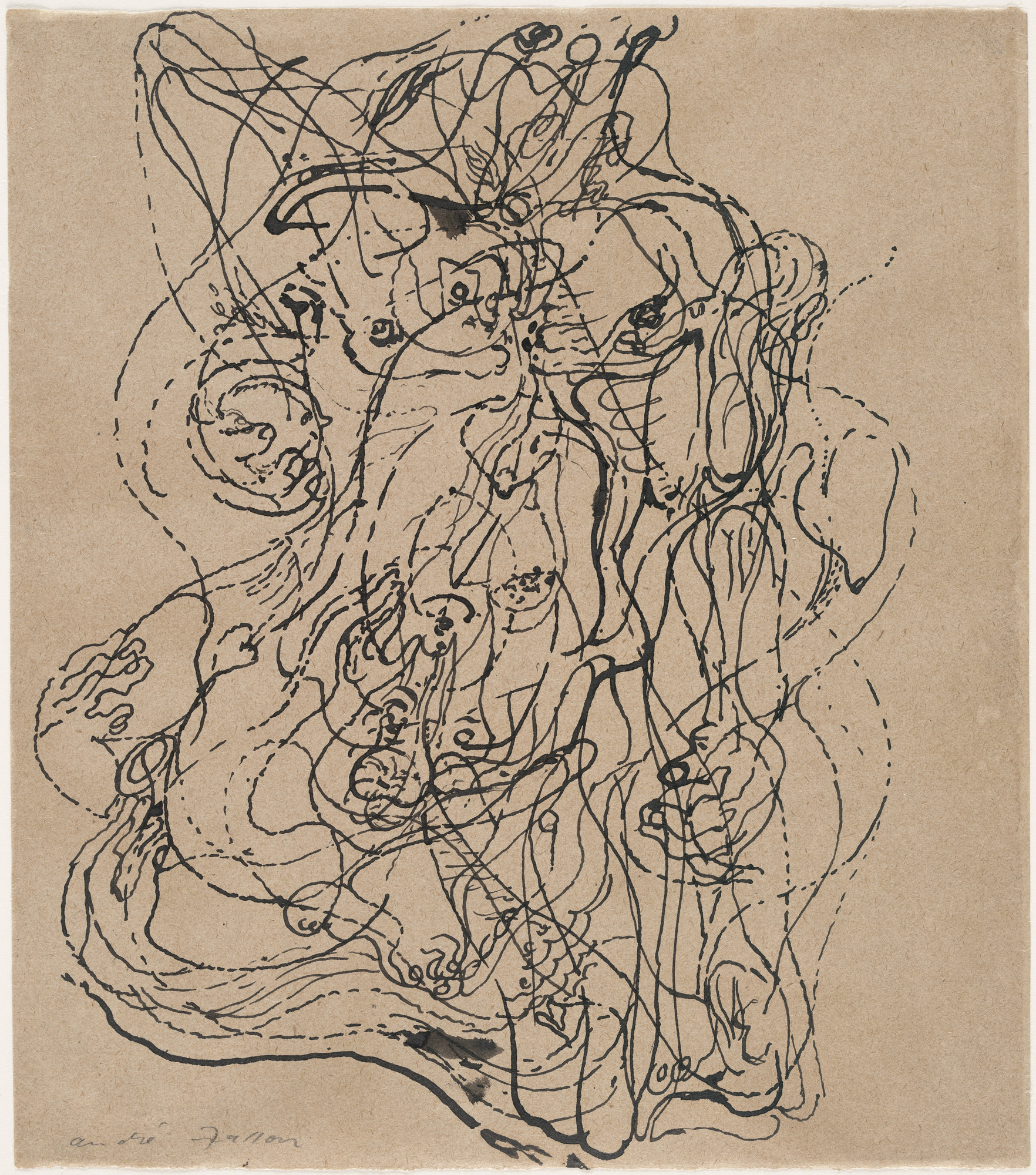

Automatism (automatic drawing/writing)

Definition: Making marks or words without preplanning to tap unconscious associations—Breton’s “psychic automatism.” Quick primer: MoMA—Automatism.

Canonical example: André Masson, Automatic Drawing (1924) — ink lines drift and knot as if thought had a hand (MoMA object).

Try it in class (2–3 minutes)

- Set a 90‑second timer. Students draw continuously without lifting the pen or planning.

- Rotate the page and look for emergent shapes—outline and label two forms you “discover.”

- Share: what did chance + memory surface?

Frottage & grattage

Definition: Frottage = rubbing with graphite/charcoal on paper over textures (wood grain, leaves); grattage = scraping wet/dry paint across textures to transfer patterns. See Max Ernst’s portfolio Histoire naturelle (1925–26) for frottage logic (MoMA overview).

Example: Ernst’s collotypes after frottage from Histoire naturelle show how chance textures spark image‑finding (MoMA—plate example).

Photograms (rayographs) & solarization

Definition: Photogram (Man Ray’s “rayograph”) = camera‑less photo made by placing objects on photosensitive paper and exposing to light; solarization partially reverses tones during development. See the Heilbrunn essay for technique context (The Met—Photography & Surrealism) and MoMA’s centennial note on Champs Délicieux (1922) (MoMA feature).

Example: Man Ray, Rayograph (1922) (MoMA object).

Exquisite corpse (collaborative drawing)

Definition: A folded‑paper game in which multiple participants draw successive parts of a figure without seeing the whole—Surrealism’s playful laboratory. See Tate—term entry and MoMA’s make‑your‑own guide.

Classroom activity (3 steps)

- Fold paper into four sections. Student A draws a head, folds to hide the drawing, passes on.

- Student B draws torso; Student C legs; Student D feet—each only sees connector marks.

- Unfold and title the creature; list 3 adjectives it suggests (dream logic in words).

Surreal object & Dalí’s paranoiac‑critical method

Definition: The surreal object re‑combines familiar things into poetic, unsettling hybrids (e.g., Meret Oppenheim’s fur‑lined teacup). Dalí’s paranoiac‑critical method involves cultivating double images and systematic, “irrational” associations—see MoMA’s object text on The Persistence of Memory for a concise note (MoMA—object page mentions the method).

Five student‑friendly works to analyze

1) Max Ernst, The Elephant Celebes (1921)

Why it matters: A proto‑surreal hybrid of machine and beast shows how collage thinking and the unconscious fuse into painting. Look for rivets, nozzle, and the headless torso silhouette.

What to look for: 1) Juxtaposition: industrial form + organic sky; 2) Scale: monumentality vs. small human figure; 3) Ambiguity: machine‑idol or playful threat?

2) Giorgio de Chirico, The Song of Love (1914)

Why it matters: Pre‑1924 metaphysical painting that Surrealists adored: a classical head, a rubber glove, a ball—logic derailed, meaning intensified (MoMA object).

What to look for: 1) Long shadows; 2) Urban emptiness; 3) Symbolic objects (antiquity vs. modern industry).

3) Joan Miró, Dog Barking at the Moon (1926)

Why it matters: A minimal, playful cosmos—ladder, tiny dog, crescent moon—invites students to decode symbols and scale jokes (see Philadelphia Museum of Art classroom PDF).

What to look for: 1) Ladder as aspiration; 2) Cartoon‑like economy; 3) Childlike mark‑making with adult complexity.

4) Man Ray, Untitled Rayograph (1922)

Why it matters: Camera‑less photography turns ordinary objects into luminous silhouettes; great for teaching negative/positive space (Met object note).

What to look for: 1) Edge halos; 2) Overlapping exposures; 3) Abstract design from everyday things.

5) René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (1929)

Why it matters: Language vs. image: “This is not a pipe.” Perfect for visual literacy and semiotics discussions (pair with art‑text debates elsewhere).

What to look for: 1) Label vs. object; 2) Painting’s illusion; 3) How words shape seeing.

Women & Global Surrealism

Textbooks once centered Surrealism on a handful of European men. Today’s research maps a global network—from Mexico City to Cairo to Tokyo—and restores the centrality of women artists. Leonora Carrington’s mythic narratives, Dorothea Tanning’s dream architectures, and Meret Oppenheim’s poetic objects stand alongside canonical names. Recent centenary programming emphasizes this broader map; see the Centre Pompidou’s 2024–25 exhibition page for the global frame and curatorial highlights (Pompidou centenary).

How to analyze a Surrealist work (student checklist)

- Subject vs. dream logic: What ordinary things appear? How are they rearranged to feel “off”?

- Juxtaposition: List two unlikely pairings (e.g., classical head + rubber glove). What new meaning do they create?

- Technique cues: Do you see automatism (free lines), a photogram (silhouettes), frottage/grattage (texture transfers), or a surreal object (assemblage)?

- Language/wordplay: Are titles or inscriptions baiting interpretation (Magritte’s paradoxes)?

- Psychoanalytic motifs: Dreams, doubles, masks, metamorphosis—where and how?

- Historical context: Can you connect it to 1924’s manifesto, 1930s debates, or 1940s exile to New York?

Background for teachers: The Met—Surrealism overview.

FAQs: quick answers students actually ask

- What is Surrealism in one sentence?

- A movement (from 1924) exploring the unconscious via dreams, chance, and free association to disrupt everyday reality (see Tate).

- When did Surrealism start and end?

- Its official “start” is 1924 with Breton’s manifesto; its influence never ends—artists worldwide keep adapting its ideas (see MoMA term).

- Dada vs. Surrealism—what’s the difference?

- Dada mocks rational culture through anti‑art and shock; Surrealism channels unconscious logic to build new forms (context via The Met).

- What is automatism? How do I try it?

- Automatism means drawing/writing without a plan to bypass conscious control: set a 90‑second timer, draw continuously, then circle two forms you “find” (MoMA—Automatism).

- What is a rayograph?

- Man Ray’s term for a photogram: place objects on light‑sensitive paper and expose them—no camera needed (see MoMA feature and Met essay).

- What is exquisite corpse and how do we play?

- Fold a page into four; each person draws one section (head/torso/legs/feet) without seeing the rest; unfold for a composite figure (see Tate).

- Why are de Chirico or The Elephant Celebes called “proto‑surreal”?

- They predate 1924 but showcase dreamlike juxtapositions and uncanny space that Surrealists adopted (see MoMA—de Chirico).

- How did Surrealism affect American art?

- Wartime exile seeded ideas in New York; Cornell’s boxes and Gorky’s biomorphic lines feed Abstract Expressionism (overview: The Met).

- Who are three key women surrealists?

- Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Meret Oppenheim—central to Surrealism’s global story; recent centenary shows foreground their work (Pompidou).

- Is this a surrealism study guide I can revise from?

- Yes—start with the timeline, learn the techniques, then use the six‑point analysis checklist to structure any exam response.

See it, then live with it

If this article sparked ideas for classroom visuals or home study corners, explore our Conceptual & Surreal Wall Art collection for evocative examples of juxtaposition, collage, and dreamlike scenes.

References & further reading

High‑authority

- Tate — Surrealism

- Tate — Automatism

- The Met Heilbrunn — Surrealism

- The Met Heilbrunn — Photography & Surrealism

- MoMA — Surrealism (term)

- MoMA — Rayograph feature

- Philadelphia Museum of Art — Dog Barking at the Moon teacher resource

- Centre Pompidou — Surrealism centenary exhibition

0 comments