Suprematism (1915–1929): How Malevich’s “Black Square” Rebooted Painting into Pure Geometry

Quick Summary / Key Takeaways

Suprematism is a radical avant-garde art movement founded by Kazimir Malevich in Russia around 1915. It pursues the “supremacy of pure feeling” by stripping images down to non-objective geometric forms—squares, rectangles, circles, and dynamic diagonals—floating on weightless fields. For a concise definition and context, see Tate’s glossary entry.

- When/where: 1915 to the late 1920s, centered in Petrograd/Vitebsk during the Russian avant-garde.

- Why it matters: It helped launch geometric abstraction and non-objective art, shaping later design education and visual culture.

- What to look for: Planar forms, diagonal tension, crisp color planes, and the feeling of infinite, gravity-free space.

What Is Suprematism? (Definition & Core Idea)

At its core, Suprematism asserts the dominance of pure sensation over depiction. Malevich proposed that painting should be liberated from objects, arriving at non-objective compositions built from elemental geometry and limited palettes. This language of reduction—black squares, colored bars, crosses, and circles—seeks an experience of feeling unburdened by narrative or representation. For a reliable overview, compare Britannica’s Suprematism entry with the Guggenheim’s movement page.

Visual grammar at a glance

- Flat color planes and sharp edges; little or no modeling.

- Orthogonal and diagonal alignments that imply motion and “lift.”

- Large fields of negative space suggesting infinite depth.

Note on terminology

Writers often pair “Suprematism” with “non-objective art” and “geometric abstraction,” especially when distinguishing it from figurative modernism.

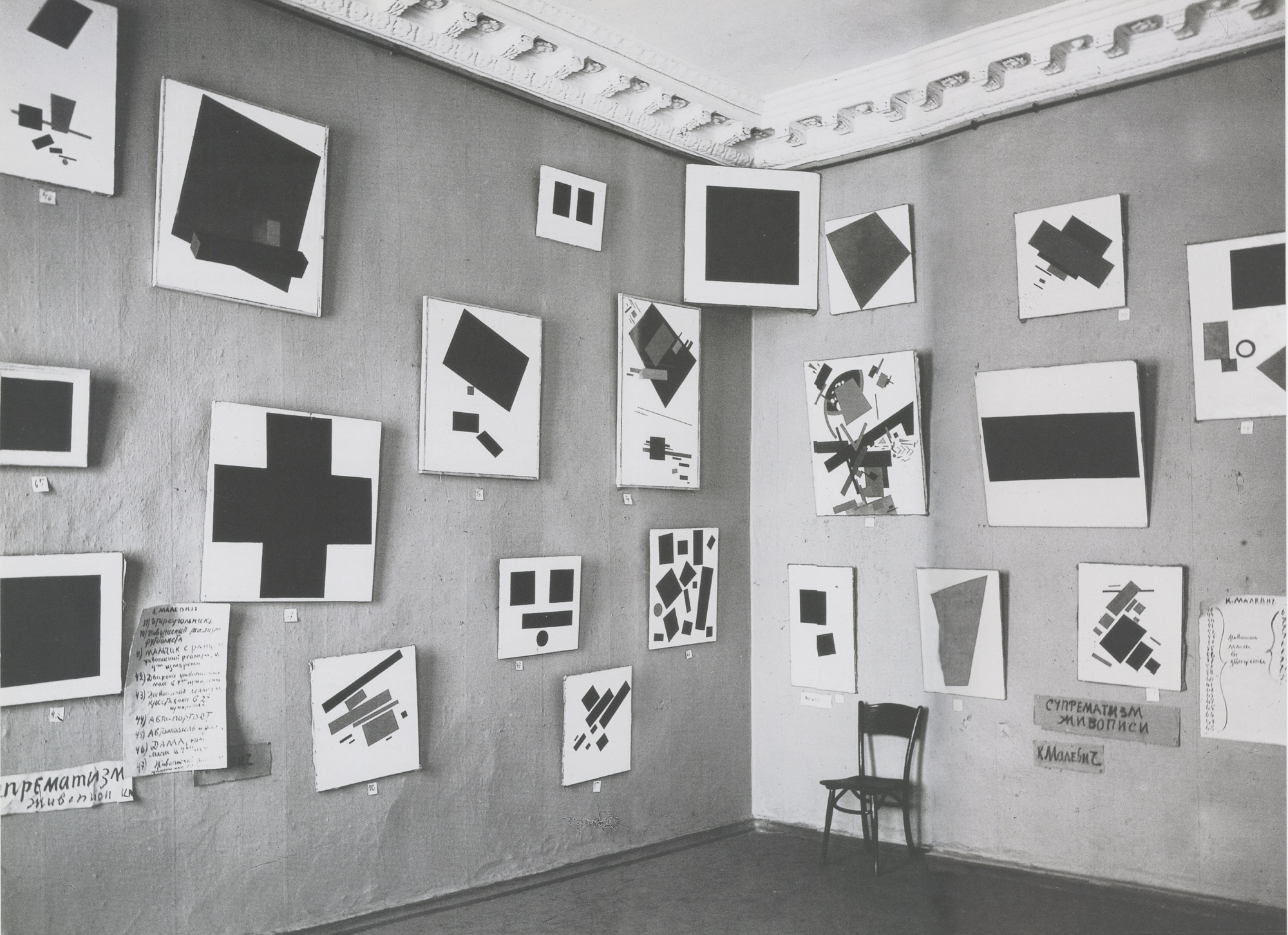

Origins: From Cubo-Futurism to the 0,10 Exhibition

Malevich moved through Cubism and Futurism before collapsing form into pure geometry. The breakthrough came at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings: 0,10 in Petrograd (December 1915–January 1916), where he presented Black Square in the room’s upper corner—echoing the placement of a home icon in Russian tradition. This display framed the work as a new spiritual “zero” for painting. For dates and context, see the 0,10 exhibition page.

The shock was immediate: by declaring a “degree zero,” Suprematism redefined painting as a field of relations rather than a window onto things. The diagonal, the tilt, and the void became active players in a new visual physics.

Five Works that Explain Suprematism

How to use this section: Read each mini-profile, then compare the angles, overlaps, and spacing. Notice how small shifts in tilt or scale can transform the sense of motion.

Black Square (1915)

More than an image, Black Square is a proposition: that painting can begin anew from absolute simplicity. Its matte field and crisp edges withdraw depiction while intensifying presence—especially when installed high in a corner. For a curator-level context, see The Art Story.

Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915)

Angles and color bars imply ascent without depicting an aircraft. The work demonstrates how diagonal tension and overlapping planes can suggest speed, tilt, and trajectory—core tools of Suprematism’s dynamic composition.

Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918)

This near-erasure strips color to a whisper. Texture and a subtle tilt become the “content,” inviting slow looking. As Smarthistory explains, the painting extends non-objectivity to its limits while preserving a felt sense of space.

Supremus No. 38 (1915–16)

Here color returns with force. Rectangles, bars, and crosses layer into a buoyant architecture that reads like a map of forces rather than a scene. The title “Supremus” signals an evolving series exploring balance, collision, and hover.

El Lissitzky, a “Proun” (c. 1920s)

Lissitzky’s Proun (an acronym often glossed as “Project for the Affirmation of the New”) translates Suprematism into architectonic thinking—rotating planes in implied three-dimensional space and pointing toward exhibition design, typography, and built form.

Artists & Circles

UNOVIS (Vitebsk)

Malevich taught in Vitebsk, forming UNOVIS (“Champions of the New Art”) with students and colleagues. The group experimented collectively across media, extending the reach of non-objective art into pedagogy and daily life. See the Guggenheim overview for concise context.

Olga Rozanova

Rozanova advanced color’s role within the movement. Her non-objective works push beyond tonal austerity toward vivid, vibrating planes—evidence that Suprematism could be both rigorous and chromatically alive. The Art Story provides a helpful primer.

El Lissitzky & Proun

Lissitzky bridged Suprematism and the emerging language of modern design. His Proun works animate space itself, prefiguring exhibition systems and graphic clarity that would resonate internationally.

How to Read a Suprematist Painting (Visual Grammar)

Tilt & Diagonal

Even small rotations create powerful directional cues. A 10–15° tilt can read as ascent, fall, or drift.

Overlap & Scale

Overlapping bars imply depth and sequence; scale jumps cue foreground/background without using perspective.

Color as Force

High-contrast primaries read as energy sources; neutrals calm the field. Saturation suggests weight.

Negative Space

Vast fields of white or off-white imply infinite space—a signature Suprematist sensation.

For descriptive support on these cues, compare Britannica with Smarthistory’s Black Square.

Suprematism vs. Constructivism (What Changed in the 1920s)

While both movements share a language of geometry, their aims diverge. Suprematism prioritizes non-objective feeling and pictorial exploration; Constructivism channels abstraction into utilitarian design, productivist aims, and social function. Figures like Rodchenko and Tatlin emphasize materials, structure, and industry, while Malevich pursues painting’s autonomous experience. Lissitzky often sits between the two, translating Suprematist insights into spatial systems and typography. A compact compare-and-contrast appears across The Art Story and Britannica.

Legacy & Crosscurrents

Suprematism’s clarity radiated outward. In design education, its reduction to basic form and color informed foundation teaching later seen at the Bauhaus. In the Netherlands, De Stijl pursued an orthogonal, primary-color rigor parallel to Malevich’s program. Decades later, perceptual investigations in Op Art reactivated geometric discipline as optical vibration.

Where to see key works today

- State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow)

- Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam)

- MoMA (New York)

- Museum Ludwig (Cologne)

From the Gallery to Your Wall

If you respond to the clarity of geometric abstraction—the floating bars, crisp planes, and sense of infinite space—browse our curated Abstract & Geometric Wall Art. You’ll find contemporary pieces that echo Suprematism’s balance of reduction and rhythm.

FAQ

- What is Suprematism in simple terms?

- It’s an early 20th-century movement founded by Kazimir Malevich that removes depiction to focus on pure feeling through non-objective geometric forms—squares, bars, circles, and crosses arranged on open fields.

- Why is Malevich’s “Black Square” important?

- Debuted at the 0,10 exhibition in Petrograd (1915–1916), it marked a “degree zero” for painting—asserting a new beginning built from the simplest possible form and a rejection of narrative representation.

- How is Suprematism different from Constructivism?

- Suprematism explores non-objective feeling within painting; Constructivism redirects abstraction toward practical design, materials, and social utility in the post-revolutionary context.

- What was the 0,10 exhibition?

- The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings: 0,10 (Dec 1915–Jan 1916, Petrograd) introduced Suprematist works, with Black Square famously hung high in a corner like an icon.

- Who were key artists besides Malevich?

- El Lissitzky (the architectonic Proun series) and Olga Rozanova (innovative color planes) were central, alongside UNOVIS collaborators in Vitebsk.

- Which museums hold major Suprematist works?

- See the State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow), Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), MoMA (New York), and Museum Ludwig (Cologne), among others.

0 comments