Futurism (1909–late 1930s): Painting Speed, Sound, and the Modern City

The futurism art movement began in Milan in 1909 with a blast of manifestos, exhibitions, and polemics that championed speed, industry, electricity, and the crowd as the new subjects of art. Led first in print by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and carried visually by Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo, Futurism recast painting and sculpture as engines of motion and sensation. It was an avant-garde that tried to picture not only what cities look like but how they feel in time, with form fractured, repeated, and propelled by lines of force.

“Futurism tried to paint what a city feels like, not just what it looks like.”

Fast Facts

Origins: Milan’s Manifesto Moment (1909–1911)

Futurism launched with a splash: Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto” appeared in newspapers in early 1909, demanding a break with the past while glorifying machinery, electricity, the press, and the pace of modern life. Within a year, painters in Milan began translating those words into images. They absorbed Cubism’s fractured planes and combined them with Italian Divisionism’s broken color to produce a visual language of velocity. Early shows in 1911–1912 carried their claims to Paris and London, turning a local Milan circle into a European provocation. At the center of this visual rhetoric was dynamism: the conviction that bodies and buildings are not static forms but fields of energy rippling through time.

Compared with Cubism’s calibrated analysis of form, the futurism art movement was unapologetically extroverted, urban, and noisy, trying to picture acceleration itself. That commitment to the mechanical city sits in productive tension with the cool structural purity celebrated by De Stijl (Neoplasticism), which focused on geometry stripped of motion.

Further reading on definition and timeline: Tate — Futurism, Encyclopaedia Britannica — Futurism, and Guggenheim — Futurism.

What the Futurists Wanted (and Why it Scandalized Europe)

In manifesto after manifesto, Futurists celebrated speed, steel, electricity, factories, asphalt, and the crowd. They called for museums to be treated as mausoleums and asked artists to turn toward the present tense — the turbine, the train, the theater, the newspaper kiosk. That rhetoric scandalized traditionalists and energized a generation eager for images that matched the tempo of early twentieth-century streets.

Their ideas mapped cleanly into visual goals. Painters “sliced” bodies and streets into directional vectors; repeated contours produced stutters and afterimages; diagonals charged compositions with propulsion; and typographic experiments leaned forward, literally slanting text to suggest tilt and thrust. The futurism art movement also flirted with aggression and militaristic language, a problematic aspect that later intersected with nationalist politics in Italy. Yet on the canvas and in bronze, the most enduring ambition was to make motion visible — to compress time into a single, vibrating image.

Key Artists & Works: A 5-Stop Tour

Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916): Body in Motion

Boccioni served as the movement’s chief visual theorist and its most inventive sculptor. In The City Rises (1910), a construction site swells into a vortex of bodies, horses, scaffold poles, and red-blue chromatic energy. Figures and architecture fuse, as if the town is being built out of velocity itself. His sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) refines the same logic into bronze: the figure is aerodynamic, all ripples and shearing volumes, cutting through air like a flame. When Boccioni died in 1916 during World War I, the futurism art movement lost a catalytic force and much of its momentum.

Giacomo Balla (1871–1958): Lines of Force

Balla’s studio was a laboratory for motion. In Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912), a dachshund’s legs, leash, and tail repeat like a photographic multiple exposure. Everyday speed — a simple walk — becomes a choreography of arcs and ticks, the quintessential demonstration of Futurist linee di forza, or lines of force. Later, Balla’s abstractions turned velocity into zigzags and arrows, pushing the futurism art movement toward pure graphic energy.

Gino Severini (1883–1966): City Nightlife as Motion

Severini brought Parisian nightlife into the movement’s orbit. Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin (1912) fractures dancers, signage, and sequins into kaleidoscopic facets that literally glitter. It’s a manifesto in paint for urban simultaneity — type, sound, motion, and light colliding in one frame. The work demonstrates how the futurism art movement absorbed Cubist structure but refused Cubist calm, preferring the club’s pulse.

Carlo Carrà (1881–1966): Crowds and Conflict

Carrà’s great subject was the political crowd. In Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910–11), diagonals slash through a mass of bodies; flags and batons collapse into wedges; the street becomes a field of force. Even as Carrà later shifted stylistically, these early canvases show how the futurism art movement tried to compress history and emotion into a single agitated plane.

Luigi Russolo (1885–1947): From Paint to Noise

Russolo painted urban agitation — see The Revolt (La rivolta) (1911), where a red-blue grid seems to buzz like a power station — and then pushed Futurism into sound. His 1913 text The Art of Noises proposed that the modern city’s roars, hums, and clatters were worthy orchestral material. He built intonarumori, noise-generating instruments, staging concerts that expanded the futurism art movement from canvas to ear.

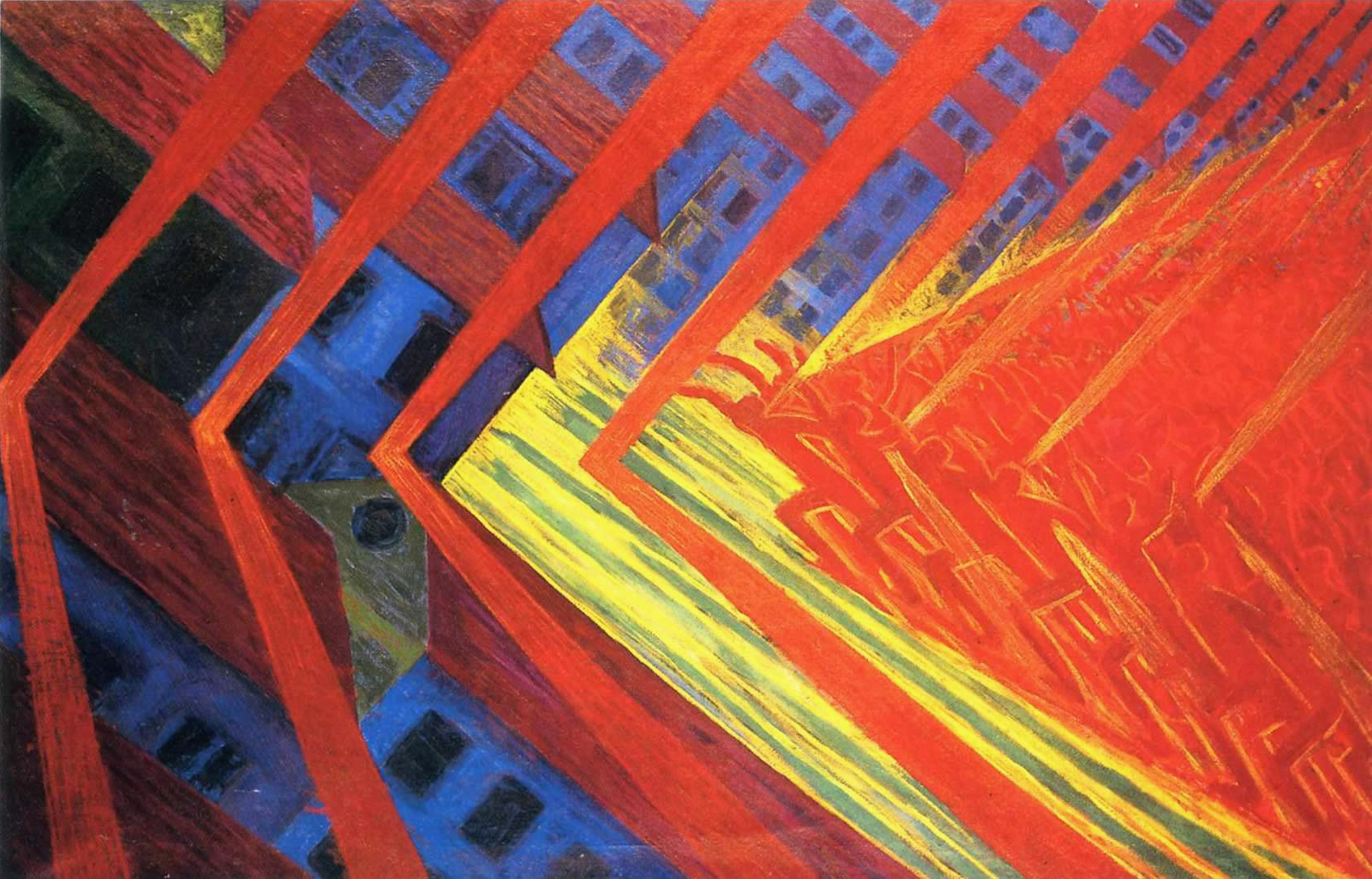

Image Gallery

A compact gallery of five touchstone works from the futurism art movement. Each caption notes artist, title, year, and collection credit.

How Futurism Looked: Techniques that “Make Motion Visible”

Futurist pictures look fast because their structures behave like motion. Repeated contours create afterimages; radiating diagonals act like force vectors; broken color, adapted from Divisionism, produces vibration on the surface. Subjects are modern and urban — streets, scaffolds, trams, dancers, traffic — but the real protagonist is time. The futurism art movement collapsed successive instants into single frames, so a dog’s paws become a blur and a worker’s stride multiplies into a fan of ankles.

At the chromatic level, Divisionism’s tiny strokes of complementary color create flicker — a perceptual buzz that later movements would explore in more abstract ways. For a deeper dive into how vision can be made to vibrate, see our overview of Op Art. Boccioni’s sculpture applied the same logic to space, shearing volumes into aerodynamic planes so that the figure does not stand in space but seems to tunnel through it.

Micro-Glossary

Dynamism

A core concept of the futurism art movement: the idea that objects and bodies are not fixed but fields of energy extended through time.

Simultaneity

Representing multiple moments in one image — a visual blend of time slices that makes paintings pulse.

Divisionism

Broken color technique (Italian Neo-Impressionism) the Futurists adapted to generate optical vibration and speed.

Linee di forza (Lines of Force)

Directional strokes or arcs that diagram power and motion; think of them as the “rails” along which energy moves in a Futurist scene.

Beyond Painting: Architecture, Music, Performance

Visionary architect Antonio Sant’Elia imagined machine-age cities with elevated walkways, multi-level traffic, and power stations treated like cathedrals of light. Though most remained on paper, these drawings articulated how the futurism art movement thought about urban form: as a dynamic system rather than a static facade.

In sound, Luigi Russolo’s 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises argued that the roar of engines, the clatter of workshops, the hum of electricity, and the shouts of crowds should enter the concert hall. His hand-built intonarumori — wooden noise instruments with cranks and levers — staged the city as orchestra. And in dance and theater, Futurists experimented with fractured costumes, strobing lights, and mechanical gestures to translate speed and tech into performance. The futurism art movement was, from the start, multimedia.

Reception, Ruptures, and Long Afterlives

Early Futurist shows shocked and attracted audiences in equal measure. European avant-gardes absorbed aspects of the program, from Vorticism’s angular power in Britain to Russian Constructivism’s machine-age poetics. World War I, however, tore the circle apart — Boccioni’s death in 1916 was a severe blow — and internal shifts saw some artists recalibrate. In the 1920s and 1930s, Aeropittura reconfigured the viewpoint from the sky, with pilots’-eye vistas turning cities into rhythmic maps of lines and arcs. The futurism art movement never returned to its pre-war cohesion, but its formal logic stayed legible across the century.

To trace those legacies: follow the line to the British Vorticists for torque and angular momentum, to Constructivism for machine-age structure, to De Stijl for geometry stripped to essentials, and to Op Art for pure perception and optical vibration. The futurism art movement was a relay point — a handoff from nineteenth-century picturing to twentieth-century sensing.

Love the way Futurism turns motion into shape? Browse our Abstract & Geometric wall art edit for clean lines, bold color blocks, and kinetic compositions designed for modern rooms.

How to Look at Futurism Today

Standing before a Futurist work, try three quick prompts. First, trace the motion lines: where does the gesture begin and end, and how do diagonals steer your eye? Second, look for simultaneity: two or more time slices colliding in one frame. Third, follow the color tempo: warm zones often read as fast or close; cool areas as slow or distant. These simple habits reveal how the futurism art movement converts time into pattern and pressure.

“Boccioni’s sculpture doesn’t stand in space — it cuts through it.”

FAQs

Further Reading

- Tate — Futurism (overview & glossary)

- Guggenheim — Futurism (movement page)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — Futurism

Explore More

Continue through twentieth-century innovation in our Art History series, or compare Futurism’s motion with the structural balance of De Stijl and the optical charge of Op Art. The futurism art movement makes both look newly legible.

0 comments