Symbolism (c. 1880–1910): Dreams, Myths & the Birth of the Modern Imagination

In the late nineteenth century, a wave of artists decided that painting shouldn’t copy the visible world—it should translate the invisible. Symbolism is that turn: from the eye to the mind, from realism to reverie. This guide breaks down the big ideas, maps the movement’s hubs, and shows you how to read five essential Symbolist works with confidence.

What was Symbolism, exactly?

Symbolism was a broad fin‑de‑siècle current—first vocal in literature, then vividly in painting—that prized the communication of ideas, moods, and inner states over the faithful description of appearances. Its artists used myth and scripture, dream logic and allegory, to point past the visible world and toward the psyche. In place of Realist “facts” or Impressionist optics, Symbolists chose metaphoric signs: the femme fatale, the sphinx, the island of the dead, the halo, the lily, the moon, the mask.

You’ll meet French and Belgian pioneers (Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Fernand Khnopff), but also Swiss‑German (Arnold Böcklin), Dutch (Jan Toorop), Austrian (Gustav Klimt, via the Vienna Secession), Polish and Baltic voices. Exhibitions in Paris and Brussels connected them, and critics used the term “Symbolism” to mark their shared refusal of positivist, purely optical art.

Key ideas you can spot at a glance

Idea over appearance

Form is simplified, stylized, or made ornamental so that it “reads” like a sign. Paul Gauguin’s Synthetism and Cloisonnism (bold contours; areas of flat color) helped many Symbolists treat the image like stained glass—clear silhouettes that carry metaphoric weight.

Subjectivity & the dream

Symbolists treat the picture as a stage for mood and memory: twilight colors; silences; apparitions. Redon’s prints called noirs show how charcoal and lithography can feel like drifting consciousness in ink.

Myth, the sacred, and the femme fatale

Instead of everyday scenes, Symbolists revived ancient stories, saints, and famously ambiguous women (Salome, Sphinx, Medusa) to explore desire, fear, and spiritual longing. Gold, halos, lilies, serpents—these become portable vocabularies of meaning.

Materials & media that matter

- Lithography & charcoal: Redon’s prints show how lush grays and deep blacks make interior states tangible.

- Oil & watercolor: From Böcklin’s atmospheric oils to Moreau’s jeweled watercolors, handling is expressive rather than descriptive.

- Decorative arts crossover: The line language slides easily into Art Nouveau posters and patterns.

Where Symbolism flourished

Paris incubated the look, but Brussels gave it a powerful network—first with Les XX (The Twenty), then La Libre Esthétique—where French, Belgian, Dutch, and Central European artists cross‑pollinated. Vienna and Munich developed their own Symbolist inflections (think Klimt’s allegories and von Stuck’s brooding dramas). In Barcelona and Catalonia, “Modernism(e)s)” absorbed Symbolist spirituality into local modern art and design.

How to read a Symbolist painting (a 6‑step checklist)

- Identify the motif: Is it a saint, mythic figure, island, flower, mask, serpent? What does that motif suggest?

- Read the light: Is illumination naturalistic—or theatrical, visionary, moonlit? (If light fascinates you, compare the Baroque playbook of tenebrism vs. chiaroscuro—and how Symbolists bend those effects toward mood.)

- Outline & silhouette: Strong contours and stylized shapes often carry meaning like letters in an alphabet.

- Color as feeling: Are colors cool and funereal, or warm and radiant? Does the palette behave like emotion?

- Source & subtext: Which legend, poem, or scripture is in play? What’s being reimagined?

- What’s omitted: Symbolists are masters of suggestive gaps. The missing “explanation” may be the point.

Contrast this with the later rational clarity of geometric modernism; for a taste of that different mindset, see our tour of Bauhaus typography examples.

Five close‑looking mini case studies

Odilon Redon, The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon…

Redon’s lithograph is both pun and poem. An eye becomes a balloon: seeing itself floats, untethered from the body, drifting over a dark sea. The medium matters—powdery blacks feel like dream‑air, not studio daylight. The suggestion (typical of Symbolism): consciousness travels, and art should follow.

Try this:

Cover the sky with your hand. The sea becomes heavier, and the eye/balloon reads more ominously. That’s Symbolist composition—tiny shifts, big moods.

Arnold Böcklin, Isle of the Dead

A boat glides toward an island of cypresses and tomb façades. No narrative is spelled out, yet everything whispers mortality. For Symbolists, architecture can do theology: walls, doorways, and columns are props for the soul. Listen to the hush; that’s the meaning.

Try this:

Trace the boat’s path with your finger. The composition pulls you inward—an enacted funeral procession.

Fernand Khnopff, I lock my door upon myself

Khnopff’s heroine leans on her hands, eyes unfixed. Around her, lilies and an enigmatic plaster head: signs of virginity, memory, and art. Belgian Symbolism often dials down drama to a whisper; meaning concentrates in motifs and posture. It’s less a “scene” than a mood that doesn’t need spectators.

Try this:

List the objects you see—then write what each might stand for. The painting begins to read like a poem.

Carlos Schwabe, The Death of the Gravedigger

A luminous angel leans over a collapsing worker in a snow‑filled graveyard. The glinting green heart turns a genre scene into metaphysics. Symbolist color is rarely “realistic”; it’s expressive—here, a transfiguring visitation.

Try this:

Squint until details blur. What stays? The emerald heart and the kneeling posture—enough to carry the whole theme.

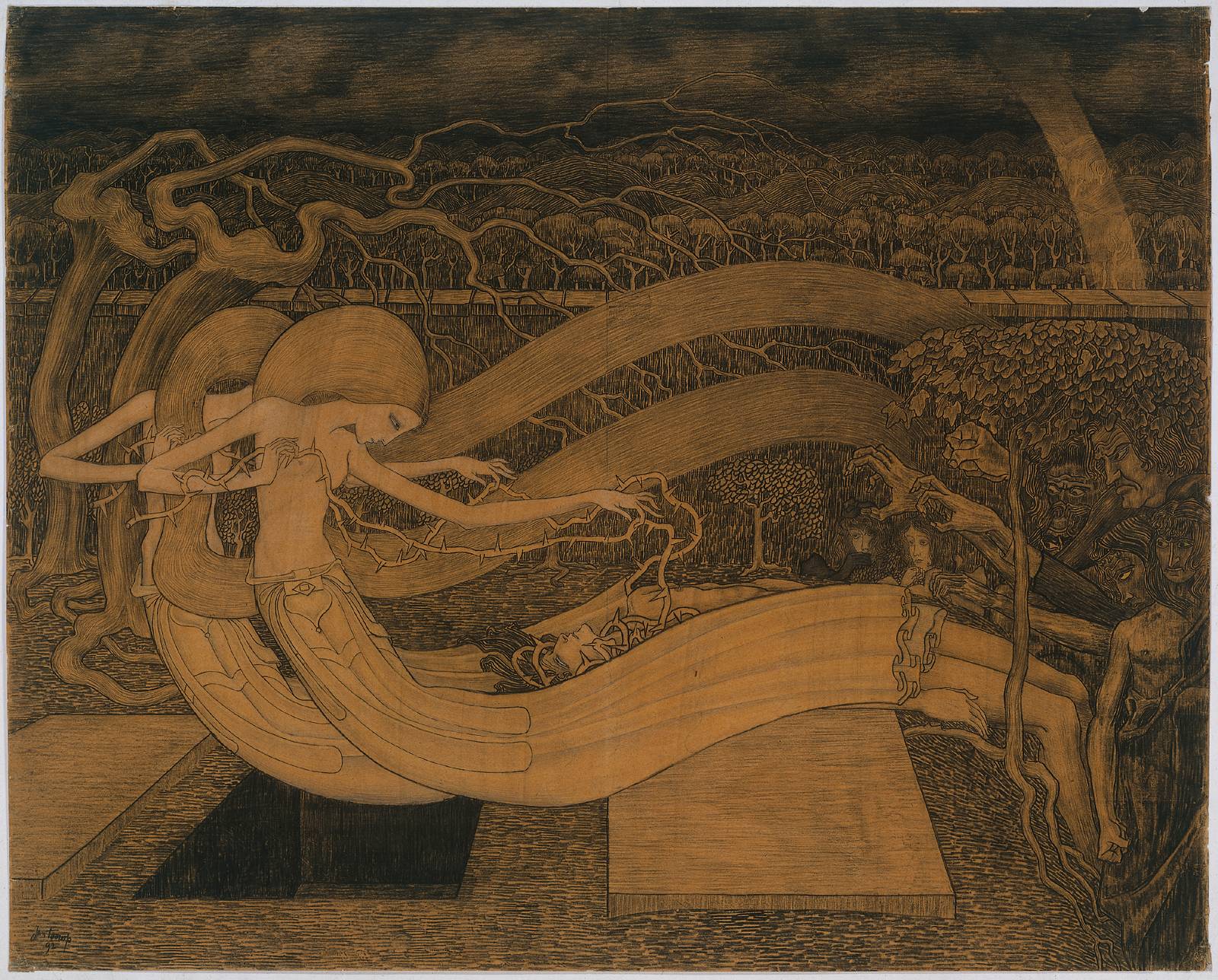

Jan Toorop, O Grave, where is Thy Victory?

Toorop’s sinuous lines—almost calligraphy—pull religious text into modern design language. That’s a Symbolist hallmark: line not only describes, it chants. Late‑19th‑century poster and book design pick up this energy and carry it straight into Art Nouveau.

Try this:

Follow any single ribboning line across the page. Notice how it loops back through meaning, like a refrain.

Legacy: what Symbolism made possible

Art Nouveau & the Vienna Secession

The movement’s saturated ornament and allegory blossomed into fin‑de‑siècle design and Viennese modernity. For a focused look at that bridge, explore our guide to the Vienna Secession (1897–1905).

Expressionism & Surrealism

Symbolism’s interior worlds and dream logic laid groundwork for artists who prioritized subjective color, anxiety, and the irrational. Track that leap—especially into the 1920s—through our Surrealism timeline for students.

Abstraction, Cubism & design thinking

When Symbolists insisted that an image can be an idea, they nudged modern art toward form‑as‑thought. Later, Cubists restructure vision into facets and signs; compare the approaches in our Analytical vs. Synthetic Cubism timeline.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the Bauhaus’s lucid geometry and functional typography—an instructive foil to Symbolist mystique you met above.

Mini timeline: Symbolism at a glance

- 1860s–70s: Proto‑symbolist imagery (e.g., Moreau’s mythic scenes) and poetic sources (Baudelaire) prepare the ground.

- 1886: In literature, Jean Moréas’s “Symbolist Manifesto” names the tendency; painters adopt the label.

- 1890s: Brussels salons (Les XX, then La Libre Esthétique) and Paris exhibitions build a network; the Salon de la Rose+Croix stages mystic‑leaning shows (1892–97).

- c. 1900–1910: Symbolist language feeds regional modernisms (Vienna Secession, Art Nouveau) and primes Expressionism/Surrealism.

FAQs

- What is the Symbolism art movement in one sentence?

- It’s a fin‑de‑siècle current that used images—myth, dream, sacred emblems—to express inner states rather than record surface appearances.

- How is Symbolism different from Impressionism?

- Impressionism studies light and momentary perception; Symbolism treats forms and colors like metaphors, pointing to ideas, feelings, or spiritual themes.

- Which artists are essential to learn first?

- Start with Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Arnold Böcklin, Fernand Khnopff, and Jan Toorop; then branch to Klimt, Munch, Stuck, Redon’s pastels, and regional schools.

- Why do Symbolist works feature halos, lilies, sphinxes, or islands?

- They’re portable signs. Halos suggest sanctity or inner light; lilies purity; sphinxes riddles and dangerous desire; islands isolation, death, or the beyond.

- Where can I see Symbolism’s influence today?

- In Art Nouveau posters and interiors, in the allegorical strain of Vienna 1900, and in the dream‑driven art of Surrealism and related modern movements.

0 comments