Egyptian Canon of Proportions: How the 18‑Square Grid Worked

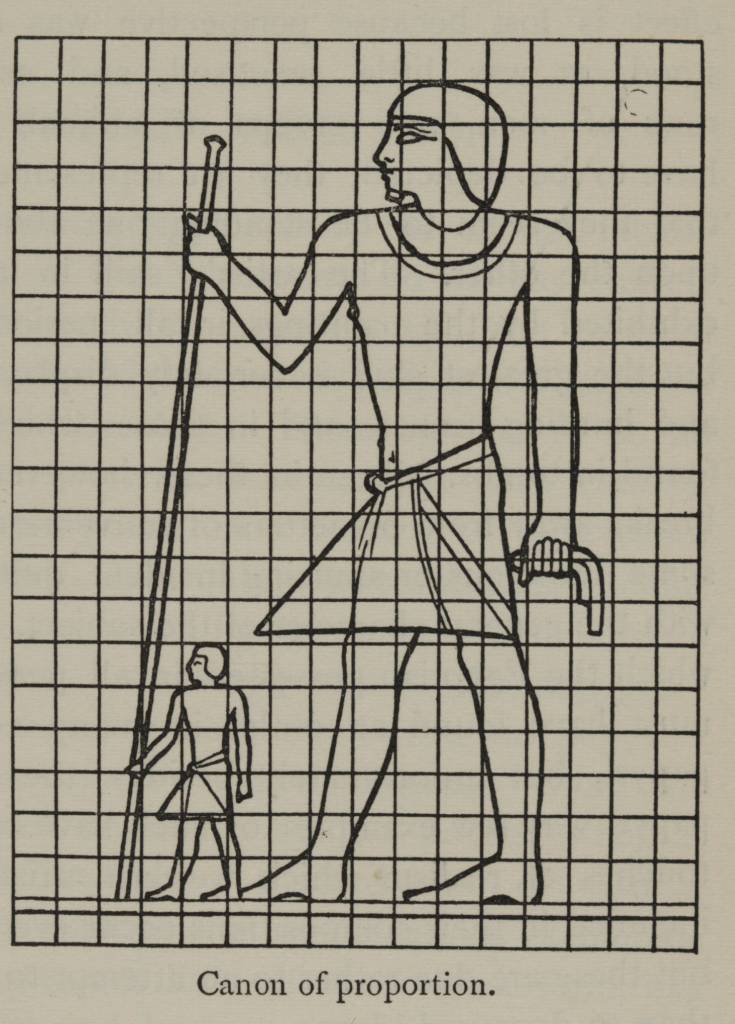

Look closely at certain Egyptian heads in profile and you’ll spot faint red squares beneath the inked contour: a workshop grid. That orthogonal lattice—most commonly 18 squares from soles to hairline—standardized bodies across three millennia. The grid was a tool, a belief system, and a workflow; later artists in the Amarna era and the Late Period widened it to ~20 and then 21 squares, fine‑tuning the canonical look.

At a Glance: the Egyptian Canon of Proportions

The canon of human proportions in Egypt is a measured scheme for placing body landmarks so figures stay consistent from tomb to temple, from painted Egyptian tomb painting to carved Egyptian relief. In the standard standing scheme, artists lay an 18‑square grid—sometimes described as an Egyptian grid—from the soles up to the hairline. Typical checkpoints fall on predictable lines:

Seated figures compress the vertical count because the lap eliminates leg height; workshops often worked with a ~14‑square unit for seated bodies. Why a grid at all? Consistency wasn’t just quality control—regularity was ritual efficacy and also made large team projects legible and modular.

For a modern echo of grids and visual order, see our De Stijl explainer on geometric reduction and right‑angle logic. Explore De Stijl.

How the 18‑Square Grid Actually Worked (Step by Step)

On plastered walls, reused drawing boards, and limestone ostraca, the process was methodical. Assistants snapped a chalked or painted cord to lay the orthogonal grid in red ochre; the master corrected contours and features in black, and carvers or painters translated the drawing into raised or sunk relief or pigment.

Try the workshop sequence

- Baseline: Snap a horizontal baseline and erect a perpendicular. Draw an 18‑square grid from soles to hairline (standing figure).

- Head block: Reserve the top squares for head and wig. Keep the profile with frontal torso in mind—this twisted perspective (a.k.a. composite view) is conceptual, not optical.

- Checkpoints: Place knee ≈ 6th, buttocks ≈ 9th, navel ≈ 11th, elbow ≈ 12th, shoulders/neck ≈ 16th. Keep the eye, ear, and mouth aligned to their horizontal guides.

- Costume & wig: Add kilt, sash, and wig as modular masses that follow the grid bands.

- Black corrections: Refine contour and details in black; adjust joints to line crossings so limbs “read” cleanly when carved.

- Transfer: For relief, prick and pounce or incise key lines; for paint, work over the red guides. Remove or thin the grid as needed.

- Seated variant: Use ≈14 squares from seat line to hairline; many landmark lines (knee, elbow, shoulders) keep proportionate offsets.

You’ll sometimes see red bands faintly beneath finished figures—the grid was never meant to be on view, but unfinished areas or gentle abrasion can bring it back.

Materials, Tools & Workshop Practice

Grids were typically drawn in red ochre (preliminary), then black ink/paint for corrections and final lines. Craftspeople used straight edges, squared cords snapped against wet plaster, reed pens, and brushes. Studios reused wood boards coated with gesso; many are palimpsests of lessons and edits. A famous drawing board—a portable training surface—still shows a red grid beneath a seated king’s outline associated with Thutmose III.

Why grids persist on objects: some work was left unfinished; some red guides were incised or painted deeply; and some surfaces were repurposed, leaving ghost lines.

From Old Kingdom to Amarna: Evolution of the Canon

By the Old and Middle Kingdoms, the 18‑square grid for standing bodies (and ≈14 for seated) had crystallized as a standard workshop rule of thumb. The system kept royal imagery stable across reigns while allowing artisans to work interchangeably on vast programs of Egyptian tomb painting and Egyptian relief.

Amarna adjustments (~20 squares)

Under Akhenaten in the Amarna period, artists appear to widen the head/neck band, effectively working with roughly 20 squares from baseline to hairline. The silhouette softens—elongated heads, fuller bellies, flexible limbs—but the grid logic remains. Archaeologists have documented fragments where the ink breaks around the hairline align to a taller count, adding ~two squares to the top band.

Late Period (Kushite & Saite): 21‑square grid

In the Kushite Twenty‑fifth Dynasty and Saite Late Period, evidence points to a 21‑square grid from soles to the upper eyelid, slightly re‑balancing head height and facial placement. Reliefs from tombs such as that of Nespekashuty in Thebes show a refined, retrospective classicism that scholars have analyzed with grid counts to compare with earlier styles.

Takeaway: the Egyptian canon of proportions isn’t a single number—it’s a family of tightly related schemes centered on the 18‑square baseline, with Amarna (~20) and Late Period (21) tweaks.

Flexibility & Exceptions: the Canon Wasn’t a Straightjacket

Even inside the Egyptian canon of proportions, artists chose what to show for clarity. The famous composite view (or twisted perspective)—profile head with frontal shoulders, then profile legs—prioritizes recognizability over single‑view optics. Minor figures can drift from the strict 18 squares when speed, wall curvature, or composition demand; sketchy ostraca reveal confident, gestural hands that ignore grids altogether.

Sometimes masters worked without visible grids; other times apprentices practiced over rigid lattices. The point of the Egyptian grid was consistency and legibility, not suppressing expression.

Why Order Mattered: Belief, Literacy & Legibility

Images did things in Egypt: they fed the dead, activated rituals, announced cosmic order. The Egyptian canon of proportions helped ensure that a king’s arm reached the offering table and that deities “read” correctly from chamber to chamber. It also enabled large teams to divide walls into coherent zones where figures, text columns, and ornament clicked into place.

For a design‑history bridge—pure geometry and planar reduction—compare the aims of Suprematism’s “Black Square.” Read our Suprematism guide.

Three Case Studies

Senenmut ostracon (The Met 36.3.252)

On a small limestone chip, the Eighteenth‑Dynasty official Senenmut appears over a red 18‑square grid. The profile and wig sit crisply in the top rows; the jaw, lips, and eye align with horizontal guides. Found at Thebes, it probably relates to the Hatshepsut court and shows how a workshop established proportions before committing to stone or paint.

Thutmose III drawing board (British Museum EA5601)

This wooden drawing board coated in plaster preserves a wiped but visible grid with a seated royal figure—vivid proof that the Egyptian grid was a teaching and planning tool. The red lattice under the king’s outline reveals how students and masters iterated on portable supports long before a wall was touched.

Nespekashuty relief (Saite Late Period)

Fragments from the tomb of Nespekashuty in the Asasif (Thebes) show a Late Period taste for precise carving and orderly fields. Scholars have leveraged 18/21‑square analytics to compare these Saite reliefs with earlier dynasties, noting the Late Period’s heightened attention to head height and facial placements in a 21‑square grid.

Coda: From Ancient Grids to Modern Design

It’s tempting to draw a straight line from an Egyptian workshop grid to the modernist classroom, but the point here is analogy, not influence. Like the Egyptian orthogonal grid, modern movements valued modularity, repeatability, and clear structure. De Stijl chased balance through right angles and reduced palettes; the Bauhaus taught design schooling, modular thinking, and type & layout grids; and Suprematism pursued non‑objective pure geometry.

See also: grids and visual order · design schooling, modular thinking, type & layout grids · pure geometry and planar reduction

Student Corner: Draw Like an Egyptian

Classroom exercise (7 steps)

- On newsprint or a board, chalk an 18×N grid (squares ≈ 2–3 cm). Mark a baseline.

- Lightly sketch the head inside the top squares; place the eye along a horizontal guide.

- Mark checkpoints: knee ≈ 6th square, buttocks ≈ 9th, navel ≈ 11th, elbow ≈ 12th, shoulders ≈ 16th.

- Block in torso (frontal), head/legs (profile) to try the composite view.

- Add wig and kilt as simple shapes that respect grid bands.

- Overlay the final contour in dark pencil/ink; add simple color if desired.

- Erase or fade the grid to “finish.”

Safety & credit: if you trace from museum photos, include object, museum, and accession in your label copy. For a printable practice sheet, see a handy Draw Like an Egyptian handout from the University of Memphis.

FAQs

What is the Egyptian canon of proportions?

A workshop rule that maps the body to a grid—most commonly an 18‑square grid from soles to hairline (standing), with a seated variant around 14 squares. It kept figures consistent in Egyptian relief and painting.

How did the Amarna period change the grid?

Artists effectively used a ~20‑square grid from baseline to hairline by expanding the head/neck band; silhouettes grew more elastic but still followed grid logic.

When does the 21‑square grid appear?

In the Kushite/25th and Late Period (Saite), evidence shows a 21‑square grid from soles to the upper eyelid, changing facial placement slightly.

Why do we still see red lines on ancient art?

They’re red ochre guidelines that were never fully removed, or that resurfaced as surfaces wore; some were incised and thus more durable.

What is “twisted perspective” (composite view)?

A conceptual stance: profile head and legs with frontal torso to show the most characteristic aspects of the body at once—clarity over optics.

What tools and pigments drew the grid?

Snapped cords and straight edges for lines; red ochre for preliminary grids; black for corrections and finals; reed pens and brushes on plaster, wood, and stone.

Did artists ever work without grids?

Yes. Quick sketches on ostraca or confident master studies could be freehand; grids reappear when standardization and teamwork mattered.

Can we replicate the method today?

Absolutely—for learning. Try the 7‑step exercise above, or use a printable practice sheet.

Notes & Sources

Key object IDs, period tweaks, and workshop practice are corroborated by museum records and teaching resources. Use the list below as footnote‑style references.

- The Met — Artist’s Gridded Sketch of Senenmut (acc. 36.3.252).

- British Museum — Drawing board with grid (EA5601, Thutmose III).

- UCL Digital Egypt — Art grids (18 → ~20 → 21 squares).

- Smarthistory — Ancient Egyptian art (canon rationale & context).

- The Met — Ostracon with grid for hieratic entries (acc. 26.3.169).

- The Met — Ceiling Pattern, Tomb of Qenamun (acc. 30.4.98).

- The Met — Relief from the Tomb of Nespekashuty (Saite).

- Amarna Project — “Fragments… with Artist’s Grid” (on ~20‑square Amarna counts).

- Metropolitan Museum Journal 50 (2015/16) — articles noting Late‑Period grid practices.

- Wheaton College — “Ancient Egyptian Grid System” (landmark placements).

- The Open University — Creative process in Egyptian art (red/black practice; snapped lines).

- TIMEA/Budge — Early canon diagram (Wikimedia).

- University of Memphis — Draw Like an Egyptian (classroom handout).

- Journal of Science and Arts (Romania) — pigments note (red/black).

One More Step—Bring Geometry Home

If the geometric logic of ancient grids fascinates you, browse our Abstract & Geometric Wall Art—a curated edit where proportion, palette, and rhythm do the heavy lifting.

Glossary

Ostracon

A chip of limestone or pottery used for sketches or notes; plural: ostraca.

Composite view / twisted perspective

Profile head and legs with frontal torso for conceptual clarity.

Orthogonal grid

A lattice of perpendicular lines used to standardize figures and text.

0 comentários